Laura Pauls-Thomas picked me up from the Lancaster Amtrak station in a bucket.

To be fair, I had been warned. “I can totally pick you up at the station!” they had texted me while I was still riding the Amtrak. “I have a car or an e-cargo bike, if you want to ride in the bucket. Haha Let me know if you prefer the basic or adventurous option.”

And that is how I came to be riding in a Yuba electric Cargo bike, whizzing through the streets of Lancaster, Pennsylvania by night. I clutched my suitcase between my thighs and felt the wind whistle through the holes in my helmet.

Their bike was motorized, so we zipped past houses while chatting about our weekend activities. Some roads face only garages making it easier for pedestrians and bikers, like us, to ride through unimpeded by cars.

When we arrived at their house, the bucket slowly began to tip over. Laura strained to keep me from tumbling out. We laughed in the twinkle of their porch string lights while their chihuahua Pinto anxiously watched from the window.

It was a memorable arrival, and one that would not have occurred if Laura had driven us home instead.

Laura had invited me to spend the weekend at their home in Lancaster so that I could learn about their work with a team of young people known as Global Shapers and their efforts for accessible active transportation.

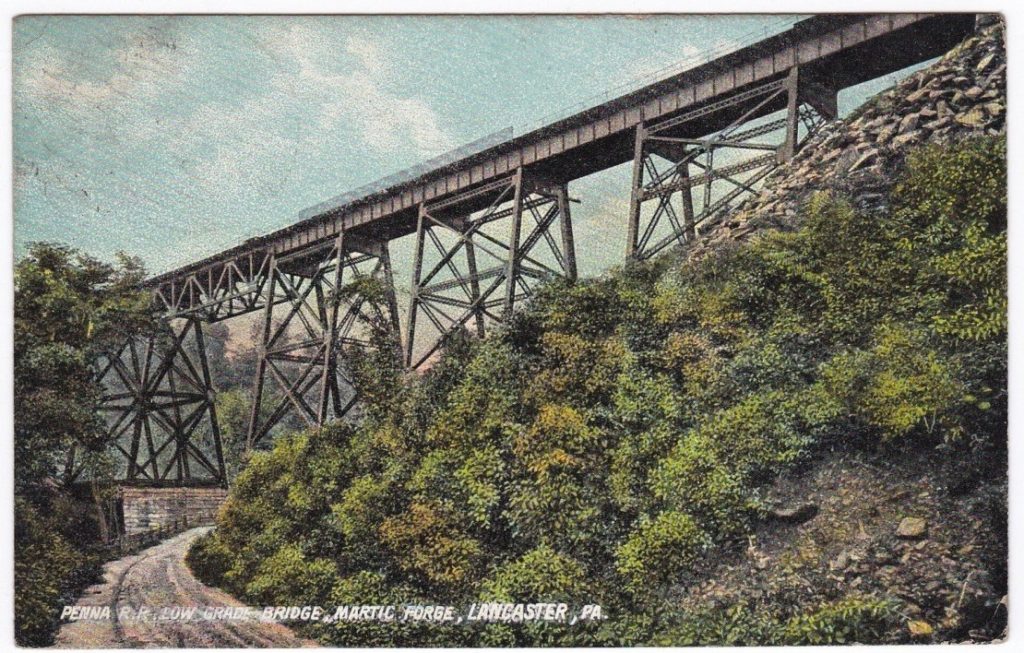

100 years ago, Lancaster was known to have one of the most advanced transit systems in the country. In 1916, Henry Justin Roddy wrote, “Few sections of the United States and no county in Pennsylvania have so complete and well-organized a system of electric car service as Lancaster city and county.” In addition to city lines, eight lines ran into the suburbs, reaching at least 12 distinct areas of the rural county and serving over 14 million passengers in the early 1910’s.

Trolley service first began in Lancaster in 1874 with a horse-drawn streetcar that later became an electrified line in 1891. The trolley helped people to avoid narrow, dusty roads in the summer and muddy blocked roads in the winter, and so it became a reliable way to transport milk and produce. Students of the Millersville Normal School would use it to reach Lancaster City. And from 1903 to 1930, one of the trolley lines took people to Pequea for summer boating, fishing and swimming.

However, riding the trolley was not without its hazards. If conductors weren’t careful they could jump tracks on their way through the mountains to the Martic Forge. Inconsistent track work caused passengers to reportedly experience “seasickness” as cars swayed back-and-forth.

(The last trolley to make the run from Lancaster to Rocky Springs).

And though demand was strong in the summertime, the offseason led to the trolley cars’ eventual termination. Following 1930, even fewer people took trolleys as governments invested in car infrastructure.

(Removal of Lancaster’s trolley lines in Penn Square).

According to Kurt R. Bell, in September, 1947, “the (Conestoga Traction Co.) took their remaining fleet of streetcars to Rocky Springs one by one, where they were turned over on their sides and systematically burned.”

Trolley car burned at Rocky Springs.

Today, several dedicated activist groups seek a return to Lancaster’s historical people-centered design rather than the car-centric design they currently face.

“A place where the only option is to jump in the car is not the kind of place I want to live,” Laura said.

Lancaster, as described by Laura, is a very walkable and bikeable city. Some of the old railways have even been transformed into biking and hiking trails. The Red Rose Transit Authority (RRTA) provides local public bus transit to the city of Lancaster and its surroundings. To the Northwest, there are historic towns, like Mount Joy, Ephrata and Elizabethtown. To the East, is the Amish and Pennsylvania Dutch Countryside. And to the South West, are the Riverlands, full of biking and hiking trails.

As a kid, Laura would bike on rail trails (railroad tracks that have been converted into bike paths) with their parents. But it wasn’t until they studied abroad in Seville, Spain in 2015 that they experienced how revolutionizing bike travel could be.

Seville has extensive and well-connected biking infrastructure including a bike share program. Biking to class saved Laura an hour and a half of walking every day. Additionally, she realized the emotional, physical and social benefits to biking.

Back at Eastern University for their senior year, Laura began to bike from their apartment to classes and the deli and farmers market where they worked.

After graduating, Laura and their husband Andrew moved to Lancaster City. Their first winter was admittedly lonely because they knew few people. But in the Spring, the couple established their first friendships through Monday evening group bike rides organized by The Common Wheel, a non-profit bike shop and community co-op.

“I realized bicycling’s capacity for building community,” Laura said.

Through quarterly zines from Cyclista Zine, FaceBook groups and email lists offering special events and discussion of transit-oriented development, Laura began to learn about the bicycle “as a tool for social change. They learned about the bike’s role in urban social justice movements, such as the suffrage movement, and its direct contribution to climate action.

Since then, Laura has commuted 15 miles to work in Ephrata by riding the bus or biking. And, one day, in 2021 while biking across Route 222, Laura came to a realization.

“I had the breeze blowing in my hair, and I realized I feel different spiritually when I’m riding my bike versus sitting in traffic on 222. Inside, my spiritual life feels more vibrant when I’m on my bike. I feel more open. Whereas when I get behind the wheel of a car, I feel this inflated sense of ego. I feel really important. I get offended when people cut me off.”

And it’s backed up by science. Scientists have observed a behavior from drivers known as “car brain.” This is spurred by a cultural inability to think objectively about cars, also known as “motornormativity.”

“Meaning, we justify more violence than we should when it’s related to vehicles,” Laura said.

Laura shared a study published in the Journal of Environmental Psychology, stating that one of the predictors for whether an urbanite will be motivated toward the common good is “mobility behavior,” including cycling.

Such teachings now inform their activism as they spread the word about active transit to other newcomers. Laura has taught visiting international volunteers how to use the RRTA and has empowered new bikers by suggesting certain bike routes or leading them on a bike tour.

“A lot of people just don’t know how to use it,” Laura said. “For a lot of people, their default is just hopping in their car, and it doesn’t have to be that way.”

And so, the morning after my arrival, Laura introduced me to what it’s like to bike through downtown en route to service at the East Chestnut Street Mennonite Meetinghouse, which Laura and her partner have attended since 2018.

A mix of denominations are represented in Lancaster, which is also home to one of the oldest Amish communities in Pennsylvania Dutch Country. The city was founded by Mennonite and Amish populations seeking reprieve from religious persecution.

On that sunny day, we biked through tree-lined streets that had become a mosaic of colorful leaves and Saint Mary’s Cemetery.

“Take up space,” Laura advised. “Let the cars see you.”

Laura’s partner Andrew was once hit by a car in a Home Depot parking lot. He was scraped up but otherwise fine. His bike, however, was dragged and totaled.

Upon arriving at the Meetinghouse for my first service, Laura clued me into the overriding themes of this branch of Christianity: peace-building, reconciliation and simple living. Oh, yeah, and four-part harmonies. There is a lot of singing involved, and the Mennonites attending that day’s ceremony had astounding lung capacity. I was out of breath by the sixth or seventh song.

Following the service, folks approached to shake my hand and welcome me. We spoke about the military-industrial complex with our neighbors. Another man approached us to discuss how one flight to Paris emits as much CO2 as the average American family emits over the course of an entire year due to energy consumption. Another woman expressed her gratitude for Laura’s work for climate justice.

Later, I would hear from Global Shaper Kelsey Gohn Irvine about how engaged citizenship like this is the norm in Lancaster.

“I grew up here,” Kelsey said. “And I didn’t realize how wonderful of a place it was to live until I came back. It is really a community that cares about keeping this a good place to live for everyone here. So people are engaged. They do show up to public meetings. There’s a huge emphasis on supporting local businesses in a way that I don’t think most communities have.”

Starting in August, Laura installed a “Creation Care Chart” in one of the Meetinghouse’s lobbies. Whenever an attendee walks, bikes or carpools to service, they are invited to place one smiley-face sticker on a paper. On our way out, Laura and I added our own stickers and snagged a couple scones.

From there, I took some time to stroll through the streets alone to get a feel for Lancaster’s pre-existing transit infrastructure. Many of the streets are named after either fruit, nuts or royalty, like Lime, Walnut and Queen Streets. Laura directed me to Lemon Street to check out their newest bike lane and Water Street, which would be expecting one soon.

I was drawn to Endo Cafe because of its bike theme. Inside, I spoke with Jamie Sitler, one of the owners and resident of Lancaster for the last 11 years. She told me that her partner and co-owner Jake had been a professional bicyclist until one day, while he was training, a car hit him and broke his back. Jake found medical marijuana and CBD useful in his recovery, and thus the couple founded Endo to sell coffee, food and CBD.

“There’s still a lot of cyclists but (making the streets) a little safer would be nice,” Jamie said.

They mainly elect to stay off the roads ever since Jake’s crash and because their children are 10 months and 4 years old but love Lancaster’s network of rail trails.

Luckily there is reason to expect further support for transportation projects. City councilor John Hursh, elected to the seat in the Nov. 7 general election, has a record of working on the issue. In 2022, he placed 20 to 30 chairs at seatless bus stops after witnessing an old woman lying on the ground near one.

“I liked that it helped someone immediately,” John said. “And it started a conversation in the long-run.”

John cited a RRTA transit development plan that stated that when users sit while waiting for a bus, their perceived wait time is less.

John describes his approach to transportation improvements as iterative, driven by data and consultation with neighbors who best know what safety improvements they would like to see.

“Amsterdam is notoriously a bike-friendly city,” John said. “People don’t necessarily realize that it wasn’t always that way. You see pictures of Amsterdam in the 1970’s, and there are cars roaming the streets everywhere. It was a decades-long process of slow, iterative changes that got Amsterdam to where it is today. And I think we need to think of it in similar terms in Lancaster.”

John identifies “low-hanging fruit” to include giving pedestrians lead time in crosswalks, enforcing pre-established parking regulations and installing infrastructure that encourages drivers to make slower, wider turns.

But activists identified one of the greatest obstacles to safer streets is the fact that some of the roads running through Lancaster are under jurisdiction of the Pennsylvania Department of Transportation (PennDoT), namely Prince, King and Lime Streets. Laura said that these streets have nice parks, shops and places to walk. However, traffic, pollution and noise from diesel trucks on these state routes inhibits local ability to enjoy.

And according to John, the majority of traffic accidents take place along these routes. He said that he has seen cars going 45 to 50 miles per hour. (The speed limit in Lancaster is typically 35 mph, according to PennDoT’s District Press Officer Dave Thompson).

“I once, in the middle of the day, saw two cars drag racing on Orange Street, which is one of these state routes,” John said. “And if they hit someone, they’re going to die. I mean, that’s going to kill someone.”

“The fact that PennDoT refuses to allow us to make the necessary improvements shows that state DoT’s are more interested in moving large volumes of vehicles at efficient speeds. That tends to be what they’re prioritizing, and that’s what’s creating the problem.”

In response, Dave commented that PennDoT cannot prevent trucks from using routes that were designed to be widely accessible.

“In the spirit of commerce and the economy it is not in our best interest or the city’s to indiscriminately restrict certain vehicles that need to use those roads,” he wrote. “State routes are intended to provide a connection to various destinations for all traffic types. When they intersect in urban environments, the purpose is the same, however it can present some challenges related to pedestrians and non-motorized traffic.”

Furthermore, PennDoT said that high-speed vehicles fall under the jurisdiction of local law enforcement.

“Speeding is an enforcement issue,” Dave from PennDoT said. “Any restrictions that PennDoT does enact are based on a true engineering need – for example, whether it’s a length-based restriction due to a turning radius on certain roads or a weight restriction on a bridge that might not be able to handle the weight of certain vehicles.”

John said that in order to begin slowing traffic along these routes, high-speed state routes should be converted to two-way. However, Dave said that the traffic congestion that would be produced as a consequence may backup cars and trucks onto local, residential streets. If Lancaster were to pursue such a strategy, Dave said that the city and planning partners would require a study, detailed analysis and funding for related, necessary infrastructure improvements.

Dave pointed to enhancements such as traffic signal upgrades, bike lanes and pavement markings at intersections as methods to improve pedestrian safety. And though in some cases they require PennDoT approval, traffic signals, bike lanes, bike boxes, crosswalks and sidewalks are usually the responsibility of the municipality to maintain because the municipality is “much more familiar with pedestrian needs and patterns,” Dave wrote.

John said that in order to begin slowing traffic along these routes, these streets should be converted to two-way.

“The fact that PennDoT refuses to allow us to make the necessary improvements shows that state DoT’s are more interested in moving large volumes of vehicles at efficient speeds. That tends to be what they’re prioritizing, and that’s what’s creating the problem.”

According to the 2020 census, over 40% of Lancaster’s residents identify as Hispanic or Latine, A little less than 40% identify as white and close to 13% identify as Black. One reason for this comes from the city’s origins and heritage of welcoming newcomers. In 2017, the BBC reported on Lancaster as “America’s refugee capital” because it resettles 20 times more refugees per capita than the rest of the nation.

Given these statistics, Lancaster has a vested interest in providing transportation options that feel good to all non-drivers, including refugees, immigrants, children, the elderly, people with disabilities and visitors, Laura said. And traffic, deteriorating air quality and the social inequities baked into car-centered infrastructure all lead Laura to believe that this shift is a necessary one.

“Safety and access to active transportation addresses the climate crisis and increases equity in our community,” they said. “Our bus system here really isn’t that bad,” Laura said. “I think people should use it even though it’s not perfect. And the more demand for it, the more public engagement there is, hopefully, the better it will become.

“I would love to see riding your bike, walking, taking the bus become more convenient than driving your car,” they said.

Laura and John are both on the board of directors for The Common Wheel, which instituted the Earn-a-Bike Program, through which youth ages 11 to 21 are trained to fix and maintain bikes, and Bikes for All, which assists underserved neighbors—like refugees and unhoused individuals—in accessing public transit and learning how to bike in Lancaster.

As it stands, it is possible to go carless in Lancaster County, but “it really adjusts how you live your life,” Laura explained.

Global Shaper Yujin Kim is currently carless. When moving back to the U.S. from Korea to attend Goshen College in Indiana, Yujin was so accustomed to using efficient and reliable public transit that she planned to do the same.

“(In Korea), it’s a very normal thing to do,” Yujin explained. “It’s great. Everything is on time. It’s a great system. And so when I came here, my first thought was, ‘Great! I can take the bus.’ It came very natural to me, but here that’s not the case for everyone. There’s not a lot of awareness around public transit and also some sort of stereotypes.”

Luckily, Laura and Yujin are not the only one driven to convince others of the wonders of public and active transit. The City published an Active Transit Plan to identify safe routes and opportunities for improvement and introduced the bike share program Bike It. RRTA is also looking to make updates to its bus routes after 50 years of largely the same service lines.

“We’re one of the few communities that’s going through a (transit) culture shift right now, and the public’s in support of it,” Global Shaper Tony Dastra said. “We’re in a car-centric society in America, and anything we can do to take these active transportation concepts and put them in practice locally, I feel is a positive.”

And then there’s Lancaster’s Global Shaper hub—a program out of the World Economic Forum’s Global Shapers community, which encourages young adults aged 18 to 30 to take an active role in solving community problems. In order to provide the public with a vision of what they could reasonably use the bus for, Laura, Yujin and other fellow Shapers began the Ride, Roll and Stroll campaign.

To drive participation in May’s National Bike Month, the Global Shapers decided to create and distribute passports in a variety of languages.

And so, people who walked or rode their bikes to one of the 15 participating locations across the county would receive a stamp. Passports were collected at The Common Wheel and raffle tickets were awarded for every stamp collected. Participating businesses donated prizes and the grand prize was a $200 gift card to The Common Wheel.

Kelsey told me that at first the Global Shapers had considered using the passports to orient newcomers to Lancaster. For instance, rather than businesses the stops would feature hospitals and grocery stores. Ultimately, the team decided to create a “fun adventure” that was more exciting for the public and one of the Shapers that works at a refugee welcoming organization is refashioning the passport for that very purpose.

Global Shapers recorded over 75 car-free rides from the 610 passports that they passed out.

“We actually had one person who visited every single stop on the passport and got all the stamps, which was pretty amazing,” Laura said.

In addition to the passport program, the Global Shapers taught people how to load and unload their bike from the front of a parked public bus that they had reserved from RRTA. And they worked with the City of Lancaster to secure a Bronze-level Bicycle Friendly status from the League of American Bicyclists.

“It has sent a pretty clear signal to city government and local elected officials that we care about bicycling in Lancaster, and it’s who we are, and it’s something that we want to prioritize in terms of transportation,” Laura said.

These projects reached 700 people by Global Shaper estimates—way more than the team expected for their first year.

The Global Shapers have also been advocating for the addition of new bike lanes. Laura said that the City is working with limited space as a historic city but one benefit is that the narrow streets, whether due to parked cars, painted lines or bollards, serve to slow traffic.

“In that way, some of our older infrastructure can work with us,” they said.

The Global Shapers presented this work to the annual Pennsylvania Interfaith Power & Light Conference—a nonprofit that mobilizes people of faith to take climate action. This year’s theme was No Faith in Fossil Fuels. The Lancaster attendees watched films and participated in workshops like Coral Rites’s Indoor Worm Composting class.

Later in the afternoon, it was the Global Shapers’ turn to lead a transit workshop entitled “Creation Care Commuting” presented by Laura, Kelsey and Tony. The Shapers spoke of how biking fit into their own spiritual practice.

“Being Mennonite, I apply my own peace theology to active transportation ” Laura said. “In terms of relationship with Creation, we all know that riding your bike is a lot more gentle on the environment than driving a personal vehicle.”

Laura pointed to Pope Francis as an example of modeled humility because, as a Cardinal in Buenos Aires, he would take the bus.

Laura said that in endeavoring to “be a good community member and more like Jesus,” going carless has supported their efforts.

They then shared a story from the previous night. While waiting for me to disembark from the Amtrak, Laura stood outside of the train station. A distraught young man approached her. He said that had missed his train home and could not afford to stay in a hotel. Laura gave him options for safe houses and shelters to spend the night.

“While there were several people waiting at the train station in cars, the man approached only Laura. If I had been in a car, I would not have had that opportunity.”

Cherry Valley’s Mayor Michael Bagdes-Canning attended the Global Shapers’ workshop. As the mayor of a borough with a population of 66, he said that his constituents don’t see how it could even be possible. His borough has a single state-managed bike trail, but he describes the other roads as “horrible” for bikers.

“On top of that, people are not used to dealing with bicyclists, so as a consequence, it’s dangerous,” the mayor said, generating some nods in agreement from other attendees. “(Drivers) don’t give you any room.”

However, Kelsey said that in her experience, Lancaster County drivers are actually more aware and able to share the road.

“You know how to pass a horse and buggy, so you know how to pass a bike rider,” she said. “That made me feel safer, and for the most part, I’ve found that that’s true.”

Tony also suggested that Michael check out Lancaster’s rail trail system. Given how unlikely it is that the railroads or trolleys will return, converting old railroads into bike trails has been seen as a long-lasting and celebrated alternative.

“Those tracts of land that have been gifted by the government are some of the most protected property rights,” Tony explained. “And so that is one way forward to reconnecting those rural communities where obviously the rail isn’t going to come back, but you can still use those pieces of land for something.”

In the long-term, Lancaster’s Global Shapers are interested in restoring transit connectivity across the entire county, not just Downtown. For the coming year, the Shapers have received a grant to expand their passport program once again in May. They also seek to create spaces to gather activists, raise awareness of the work that is already being done across groups and increase collective capacity to make change happen.

“There’s a lot of different groups here and a lot of different community leaders who don’t necessarily know each other and don’t talk,” Kelsey said. “I think, as the Shapers having these kinds of events, we can bring some of those folks together to have a little more coordination in terms of our advocacy.”

Additionally, Kelsey said that the team hopes that their work will spark other projects and plans to begin a mini-grant program for projects such as teaching children how to bike or orienting new Lancaster residents to the transit system.

Leave a reply